Mass Manufacture Acoustic Neck Joints

I should definitely preface this post by stating that what follows is my opinion only. It may be that I’m alone in these views or it may be that other guitar builders and repair-techs agree. The post below, however, is my take on things.

I recently had a Tanglewood TW130 through the shop for repair. It’s a nice little acoustic—I’ve always been a sucker for all-mahogany acoustics. The guitar had taken a fall and the heel had come away from the body. I’ll detail the steps taken to assess and repair this damage in a later post but I wanted to discuss the guitar’s construction as a separate issue.

Before I get to that though, a little primer on acoustic guitar neck joints. Bear with me…

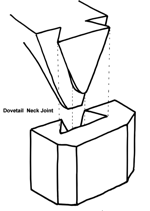

The Traditional Dovetail Neck Joint

Historically, acoustic guitars had their necks fixed to the body with a dovetail joint. This is a very strong joint and when glued is damned solid. The dovetail is considered the ‘traditional’ neck-joint and it tends to be more prized by many who consider it imparts a superior tone to the guitar. A good dovetail joint tends to require a little more work and care to accomplish well though, and it makes for a little more work when performing a neck-reset on an older guitar.

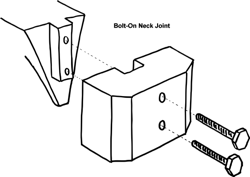

The Bolt-On Neck Joint

For these reasons (and possibly others), many modern guitar makers use a bolt-on neck joint. In this joint, a short mortice and tenon is cut in the neck block (in the body) and in the neck. This is used mainly for alignment purposes although it provides some strength. Most of the joint’s strength, however,  comes from the bolts that are attached, through the neck block, into threaded sockets in the neck heel. These tighten to pull the neck securely into the body and, questionable arguments about tone aside, provide a strong, solid joint. And, when it comes to setting the neck at some stage in the future, it’s much easier to undo some bolts than it is to steam out a glued-in dovetail.

comes from the bolts that are attached, through the neck block, into threaded sockets in the neck heel. These tighten to pull the neck securely into the body and, questionable arguments about tone aside, provide a strong, solid joint. And, when it comes to setting the neck at some stage in the future, it’s much easier to undo some bolts than it is to steam out a glued-in dovetail.

The New Neck Joint?

This Tanglewood doesn’t use either of these methods, however.

This guitar has a quite small neck block (the part that the neck usually bolts or dovetails to) and has a slightly larger than usual support under the fingerboard extension. The reason for this latter is that there are channels cut here to accept the truss-rod (in the middle) and two square, box-sections of steel on either side. It’s these steel sections that—glued into the channels on top of the guitar—that provide the bulk of the joint’s strength.

You can see three dowels poking out the front of the neck block/body—one of these is wooden and two are plastic. In my opinion, their primary role is alignment as they’re not going to provide much support.

The face of the neck-heel—where it butts against the body—is a glueing surface on this guitar and I guess this was considered sufficient support when combined with the dowels and channels. I’ve a couple of problems with this.

- String tension does a mighty fine job of trying to pull the headstock of a guitar down to meet the bridge. Poor support along the heel area can only make this job easier. Think of a long-bow. The tension of the bow-string pulls the bow into that arched (bow) shape. That’s what the strings are doing on your guitar too. The poor thing needs all the help it can get to resist those damn strings. One knock was enough to break the (slightly brittle) hold this glue had.

- Dovetail and bolt-on neck joints both pull the neck snugglyinto the body. As well as strengthening the joint, this can only help tone and string energy. The Tanglewood’s neck is, effectively, sitting on the body with a bit of glue and a couple of pins holding it in place.

- While it’s fair to argue the practicalities of the owner of a lower-cost guitar deciding to plump for a neck-reset at some stage in the future, should that happen, legitimately disassembling this sort of joint would (perhaps counterintuitively) be much more problematic than what was achieved with a simple fall in this case. As it happens, reassembly is more difficult too.

Now, I’m not being elitist here. This is not a guitar that cost thousands and there are many valid reasons for manufacturers to economise where they can. I’ve owned, played and repaired many cheapies and budget instruments in my time and many have been absolutely fine (and some have punched brilliantly above their weight). I’ve no idea how much money was saved in the manufacture of this instrument in this manner rather than with a regular bolt-on neck and I’m slightly conflicted in passing judgement as it’s great the there is now such a selection of fine instruments available for peanuts. It certainly wasn’t the case when I began playing guitar.

Personally, though, I can’t help feeling that the decision to go with this joint over a regular bolt-on has compromised this instrument. At very least, I feel it’s durability, and therefore longevity, is compromised. I don’t think that’s a good thing on any instrument, no matter how much it costs.

What do you reckon?

This article was brought to you by Gerry Hayes from the workshop of Haze Guitars and is cross-posted there. Haze Guitars provides guitar repair, restoration and upgrade services and makes beautiful, hand-built instruments